Augustine said we shouldn’t be all that impressed.

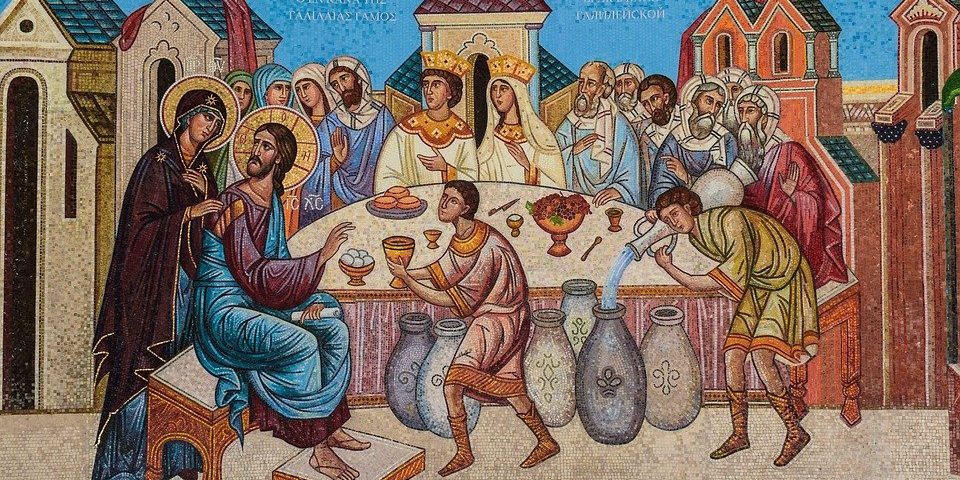

That Jesus “made wine out of water is not all that astonishing,” he said. “[W]hat the clouds pour out is turned into wine by the work of the same Lord,” he pointed out, all the time in vineyards all over the world.[1] If we weren’t so blinded by familiarity, he suggested, we would be just as amazed by the everyday working of the world as we were by the signs and miracles of Jesus. Chesterton said something like this in his Orthodoxy, that he “always vaguely felt facts to be miracles.” For Chesterton, the world clearly exhibited some sort of purpose and therefore suggested some person—“if there is a story,” he said, then “there is a story-teller.”[2] Thus, contemplating Jesus’ turning water into wine at a wedding at Cana, we needn’t waste too much time asking questions about the fact of the miracle itself but more about what it means, the deeper meaning of what John called the “beginning of his signs.”[3] That’s what’s more important—what it means. “[H]e was suggesting something to us,” Augustine said, “some mystery…is hidden in the deed.”[4] Like some sort of secret language, God speaks to the faithful in this mystery. The Father speaks of his Son, and divine knowledge brings with it the promises of destiny, our blessed end, our perfection, our happy home.

Of course, saints and theologians have for centuries reflected upon this first of Jesus’ signs, and have extracted from it all sorts of things—some of them profound and others plainly nonsense. Staying with Augustine a bit—and with all due respect to the good doctor—his meditations on the wedding at Cana are at times a bit of a theological snipe hunt. In this story he found arguments against Manichean heretics;[5] in the amount of water in the jars he found arguments in favor of the Trinity; and in the six jars of water he discerned the six ages of man—some of this, as I said, is plausible, some of it fanciful. The great Origen found in this story justification for the way he interpreted scripture.[6] Augustine again, and Cyril of Alexandria along with him, saw in this story God’s approval of marriage—an interpretation which has stood the test of time, finding a place even in our own contemporary Rite of Marriage.[7] The story of the wedding at Cana is rich indeed. By simply calling it a “sign,” John indicated that some meaning was meant, some word, some revelation. And we remain, even after all these many years, and if we haven’t given into the spiritual lethargy of familiarity, in wonder. He “revealed his glory,” John says at the end of this story, “and his disciples began to believe in him.”[8] And so we, wanting to see something of that glory ourselves, stand before this mystery too—wondering, waiting, hoping for a little bit of the truth—just enough to lighten our path and inspire us along the way.

But what are we to make of this sign, of Jesus turning water into wine? It is the Jewish context of this story which provides, I think, the best clues for understanding what’s going on here. The early fathers sometimes didn’t have the breadth of research to hand which we take for granted today (no Google in the fifth century), nor were they particularly inclined to think first of the Jewish background of particular texts. And in this story the Jewish context is important, especially the cultic and prophetic background. All of it comes together as sort of a scriptural masterpiece, a genuine revelation which gives us even today a spiritual lesson and hope—relevant hope which can strengthen our souls.

We discover something significant immediately when we learn from the Old Testament prophets how they hoped for the future, how they imagined the final fulfillment of God’s plan. In short, what they dreamed of was abundance. When Jeremiah dreamed of the restoration of Israel and Judah, he imagined everyone ascending the heights of Zion. “[T]hey shall come streaming to the Lord’s blessings: The grain, the wine, and the oil.” God will give “fat” portions to the priests, and all of God’s people will be filled with blessings.[9] Joel dreamed of a day so abundant that all the mountains would “drip new wine” and all the hills “flow with milk.”[10] Amos imagined the same; and since he was a farmer, he imagined also a time so agriculturally rich that one would plant and harvest one’s crop all on the same day.[11] And all this abundance of course called for a party, a banquet, a feast. This is what Isaiah saw. “On this mountain,” he said, “the Lord of hosts will provide for all peoples a feast of rich food and choice wines, juicy rich food and pure, choice wines.”[12] There’s a very late apocryphal text that takes this to the extreme, imagining that in the messianic era each vine will have a thousand branches on it, each with a thousand clusters, each cluster with a thousand grapes, with each grape giving over a hundred gallons of wine—quite a party![13] This is how the prophets saw the future and the fulfillment of God’s plan for the faithful. And, of course, they also saw this in terms of love—God’s love for us finally consummated on that great and final day. It’s the beloved, the “lily of the valley,” isn’t it, who said of her lover, “He brings me into the banquet hall…Strengthen me with raisin cakes, refresh me with apples, for I am faint with love.”[14] Abundance, and love, and feasting: these are the dreams of the prophets, our ancestors through whom God spoke in partial but in beautiful ways.[15]

Now we can understand perhaps why John points out that Jesus turned so much water into so much wine—upwards to 180 gallons—and good wine too, the best for last, just as the prophets imagined. And it is not insignificant that he performed this sign at a wedding, confirming not only God’s approval of earthly marriage but also signaling that the Beloved is come, God in Christ come to marry his bride Israel, the Church. Here we see at Cana a sign of the new messianic kingdom begun in Christ, the beginning of what the prophets strained and begged to see, a mystery given to us today, millennia in the making and never-ending. Here we see at Cana the beginning of our mystery, the Church. We see ourselves in this wedding sign. If we look with a spiritual eye, we discover that this is our wedding and our marriage. That’s what John meant when he said at the end of Revelation, “The Spirit and the bride say, ‘Come.’”[16] It’s a profound mystery. If we pass over it too quickly, we’ll miss it, but if we pray in silence before it, we’ll be changed, transformed by divine love.

But there is something else we should learn here, something that touches us right where we are as worshipping Catholics. In the catacomb of Saint Peter and Saint Marcellinus in Rome there is a small collection of frescos over one of the many vaults which depict three New Testament scenes together. On one side of the vault is an image of Christ at the wedding at Cana, touching the six jars of water with a rod of some sort. On the other side of the vault is an image of Christ multiplying the loaves, a miracle recorded in all four gospels. And between these two images, as if connecting the story of Cana and the multiplication of the loaves, is an image of the heavenly banquet, of heaven.[17] Here we see how many in the early Church interpreted the Cana story. They saw in this story the mystery of the Eucharist. Just as bread was given in abundance after Jesus noticed, as Mark tells it, that they “have nothing to eat,” so too at Cana wine is given in abundance after the Lord’s Mother comes to him to report, “They have no wine.”[18] And all of this happened around the time of Passover; the same time of year, just a few years after the wedding at Cana, when Jesus gathered his disciples for his final meal, saying forever that night “this is my body” and “this is my blood”—bread and wine now body and blood in abundance—at first a sign at Cana, now a reality on every Catholic altar throughout the world, even our altar, even today.[19] And as I said, Jesus spoke these words eternally. We are talking about a feast, the prophets will remind us, and a feast always points to the fullness of time. We cannot think that we simply remember what happened at Cana, nor can we think that we simply memorialize what Jesus did at the Last Supper. It is eternal and ever-present because, plainly, it is God who gives us these words, his body and blood. St. John Paul II talked once about a “‘mysterious oneness in time’” linking every Eucharistic celebration with the Lord’s Passion.[20] Or as the Catechism says, all of this “participates in the divine eternity.”[21] It is the Risen One who speaks, we should always remember, and so his words are not locked in the past. He speaks today just as he ever did.

What then will you see, when in a few moments, I stand before you, holding up for all of you to see, the Sacred Host and the Precious Blood? What then will you hear, when I say, “Behold the Lamb of God, behold him who takes away the sins of the world. Blessed are those called to the supper of the Lamb”? You will indeed see Christ, body, soul, and divinity, but won’t you also see something of your destiny? Won’t you also see something of the fulfillment of all history and meaning? What is the “supper of the Lamb”? God has guided and loved and carried his faithful people since the very beginning, and he intends to carry us to the very end, that beautiful end. And how does he carry us? It all begins with a simple priest and his simple invitation, “Lift up your hearts.” And with the simple reply, “We lift them up to the Lord.”[22]

But what difference does this make today? Is this just the soothing opiate our critics describe? Is the Eucharist just about dreaming of the future? How does this change us? Pope Benedict, said something about this once, that “Worship gives us a share in heaven’s mode of existence, in the world of God, and allows light to fall from that divine world into ours.”[23] What he meant, of course, is that because of the Eucharist, we’re given the grace to live like we’re in heaven now. Because of the Eucharist, we can truly be brothers and sisters to one another now. Because of the Eucharist we can live without fear, without the fear of death, without the fear of anything. Our life is hid with Christ in God, Paul said.[24] And so, we can begin heaven now. Cana signaled the messianic kingdom. The Eucharist signals our new heavenly reality. Our task is to be the sort of people with spiritual eyes open enough and focused enough to see these mysteries, mysteries that have never faded but are as brilliant as ever. If you can’t see it that doesn’t mean it’s not there. It means your spiritual sight isn’t very good. Do something about it. Open your eyes. See what Jesus did at Cana. See what he does today, so you can see what he will do when he comes again on the clouds with his angels. Amen.

[1] Augustine, Homilies on the Gospel of John 8.1

[2] G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy, 61

[3] John 2:11

[4] Homilies on the Gospel of John 8.3

[5] Ibid., 8.5-6; 9.6-16

[6] Origen, On First Principles 4.2.5

[7] Augustine, Homilies on the Gospel of John 9.2; Cyril of Alexandria, Third Letter to Nestorius; Rite of Marriage 127

[8] John 2:11

[9] Jeremiah 31:12-14

[10] Joel 4:18

[11] Amos 9:13

[12] Isaiah 25:6

[13] 2 Baruch 29:5

[14] Song of Songs 2:1-5

[15] Hebrews 1:1

[16] Revelation 22:17

[17] Geoffrey Wainwright, Eucharist and Eschatology, 43

[18] John 2:4

[19] John 2:13; 6:4; 13:1

[20] John Paul II, Ecclesia de Eucharistia 5

[21] Catechism of the Catholic Church 1085

[22] The Roman Missal

[23] Joseph Ratzinger (Benedict XVI), The Spirit of the Liturgy, 21

[24] Colossians 3:3

© 2022 Rev. Joshua J. Whitfield