To listen to this homily click here!

I used to love watching televangelists, the crazier the better really.

In high school I watched Dr. Gene Scott out of California. Between lectures he’d sit down while women in bikinis danced on stage. Afterwards he’d demand money for his prize horses and speed boats. Even as young man I thought, “How could people fall for this? Or sometimes even, “How can I get in on that?” But people did fall for it; he was a very rich man. I also watched Peter Popoff early in the morning selling miracle water, so obscene it was entertaining. I especially liked end times televangelists: Dr. Jack Van Impe, for instance, profitably predicting the end of the world for decades, while Dr. John Hagee in San Antonio preached in front of giant charts and maps, unraveling the mystery of history, about what’s coming our way and about who’s going to get theirs in the end. Entertaining as I said; I’m still fascinated by them in a train wreck sort of way.

But of course, what bothers me about these preachers (you might be surprised), what I consider obscene, is not their apocalypticism, their urgent insistence that the end of the world is nigh. The sooner the better, I say. Really, I wish I could go along with them. I wish they were right. However, I know that the Church in her wisdom has always corrected those who over-confidently predicted the world’s end. Thomas Aquinas, for example, was quite frank about it; he asked simply, if God chose not to reveal such knowledge to the apostles, then why would he reveal it to you?[1] Quite so, Dr. Hagee, quite so. I’ve always wondered what the Angelic Doctor would say to such preachers—Sed contra, he would no doubt begin.

Nonetheless, I’m not really bothered by talk of the end times; it’s biblical. Amos, for instance, talked about it urgently. For him judgment was coming, and soon. “Israel, prepare to meet your God!” he said full of fury.[2] Today’s passage comes to us from within Amos’ vision of the end of Israel, of the silence of death after the songs of superficial worship had been turned into the wailing of the unforgiven.[3] In Luke we get a sense of the same, the manager in the parable, as will the Father soon, demands an accounting. The whole bent of the gospel is toward the coming of the Son of Man, his final day when lightning will light up the sky.[4] For biblical people it’s nothing special to think the end is nigh; it’s why I don’t criticize the televangelists about this even though I think they’re wrong.

What I find obscene, however, is the difference these televangelists think such claims about the end of the world make. For them, for the most part, that the end of the world is nigh means that individuals ought to get right with God, that they ought to sign up to the right ideas about God and Jesus. For them, that the end of the world is coming means that as many people as possible ought, before the clock runs out, to pray the “Sinner’s Prayer.”

Now, I have no particular issue with that prayer, nor with getting your life in order. But I do wonder why salvation is cast in such individualistic terms, often solely as an individual conversion to a saving and secret knowledge that will make for your success, often described financially?

I’m curious, because when the Bible talks about the end being nigh, judgment drawing near, other things are usually considered more important than just getting individual beliefs order. When Amos talked about the advent of the wrathful God, for instance, he didn’t tell the rich people of Bethel simply to get their theology right. Rather, he said very impolitely: you’re cheating the poor, selling them for sandals.[5] God will not forget that. They thought their religion was good, but insofar as they cheated the poor, it was fraudulent; look for the word of the Lord as sincerely as they want, he said, they’ll never find it.[6] Active in religion, saying and doing all sorts of religious things: it’s nothing more than a charade inasmuch as you neglect those whom God loves, that is, the poor.

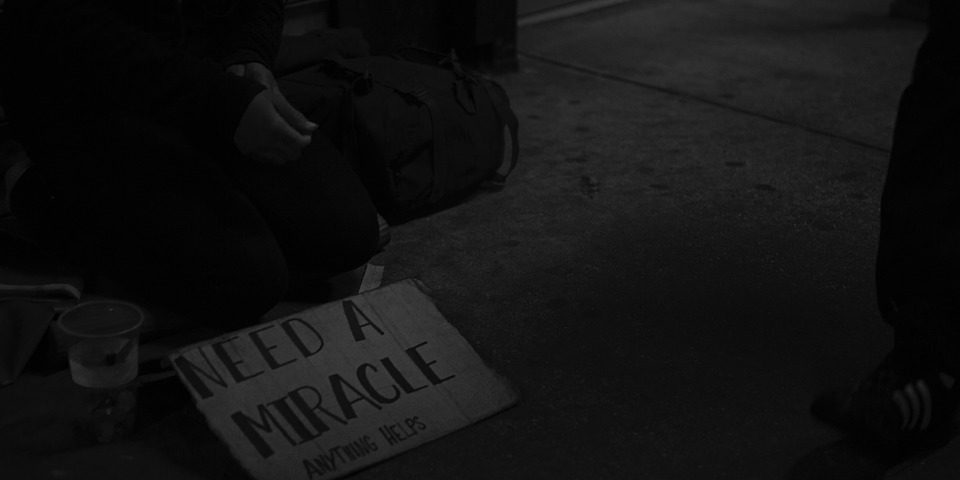

In Luke, much the same. That Christ has come, that the end is nigh; it’s not just a demand that you get your theology in order. It’s not just an invitation to have your individual crisis of conscience about the existence of God. Rather, the urgency of the end times is about the friendships necessary for heaven, about the friendships you and I need to make, literally, for heaven’s sake. That is, just as God deigned to abide with us, so too we ought to strive to abide with others. Just as God chose to dwell with the miserable (that is, you and I), so too we should choose to make friends with the despised and miserable, the invisible and the poor.

But we like to be friends with important people, successful people, not the down and out. Most of us choose our associations and friendships by different standards. Wealth, fame, status, success, the in-crowd; we drop names, cultivate associations we think will impress. We gather around importance and significance as if it is important and significant. If there ever was an idolatry peculiar to us, this is it. This is what we do, so many of us in beautiful North Dallas; even I get swept up in it. But it is not Christian. And it never will be.

Brothers and sisters, here’s the point. This is what Jesus wants us to hear. Listen to his words: “make friends for yourselves with dishonest wealth, so that when it fails, you will be welcomed into the eternal dwellings.”[7] With the wealth that you have, make friends—friends that will last, Jesus says. That is, what we ought to be about is the cultivation of friendships that will endure beyond the grave, into heaven. Why do you make money? To be independent? Carve your own space in the world? Build your castle, your dream house? Get that car you’ve always wanted? Why do you struggle so hard in the ways of Mammon? These are questions Jesus has already answered; it’s just we’ve gone a bit deaf to this bit of the gospel; selective listening, we do that sometimes to people we love but don’t want to obey, like teenagers who say, “I forgot.” Christian people are not discouraged from making money justly; it’s just that they’re encouraged, obligated even, before the judgment comes, to use their wealth for the building up of friendships that will count in heaven.

But who are these that should be our friends now and then in heaven? The poor, obviously, as I said. It’s the poor and neglected that we should make our friends, devoting to them our care, attention, and resources. And not proudly, but humbly. We must not, as we sometimes do, patronize the poor, imagining their poverty in terms of their supposed sins and failures compared with our supposed virtues and successes—that’s a lie. Nor must we refuse the poor charity, justice, and mercy because of what we think they might do with what we give them—that’s a sin. Rather, we must speak what Saint Gregory the Great once called the “language of heaven,” speaking and thinking of the poor genuinely as brothers and sisters—as real friends, really acting like it.[8]

God came to us in Jesus; we must therefore go to the poor and invisible in Jesus’ name. This, and not what the televangelists say, is what we are to do as we wait for the second coming of Christ. This is the truly biblical appeal. And it’s an urgent one, not one we can safely ignore, no matter how sentimentally we pretend our Christianity. We will hear more about this next Sunday: about the chasm between heaven and hell, between the rich man and poor Lazarus, a chasm made eternal and fiery simply because the rich man was content with that chasm in his life. It’s an invitation as well as a warning; that we should be friends with the poor; that’s the gospel, pure and simple.

Simple, then, are the questions we should ask ourselves: Who are our friends? How’d we pick them? How’d they pick us? What do we think Jesus would say about the friends we have now, honestly? Are we not idolaters of the lesser gods of our cruel, pretty world? Might not the poor we neglect now, judge us then? Jesus suggests they will. Please hear me—if but for a moment—before you ignore the preacher again, before you go back that false, sentimental religiosity which you may love now but regret later. Friendship is the beginning of heaven, but only if it’s heavenly, a thing of pure charity. Again, I hope you hear me. And I hope I hear myself too. Amen.

[1] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae Supp. 77.2

[2] Amos 4:12

[3] Amos 8:2-3

[4] Luke 16:2; 17:24

[5] Amos 8:6

[6] Amos 8:12

[7] Luke 16:9

[8] Gregory the Great, The Pastoral Rule 3.21

© 2019 Rev. Joshua J. Whitfield