It’s the great tradition.

From Egypt in the seventh century, just before the Arab conquest (when Egypt was still Christian), scholars have found the tax records of a place called Hermopolite nome—“nome” is to Egypt as a county is to Texas, an administrative district. The records give a detailed description of property ownership and things like that, offering a glimpse of the ordinary ancient world.

Now what’s remarkable about this particular “nome,” this ancient “county” in ancient Egypt (and why on earth I’m talking about it in homily) is that it gives us a picture of what Christians were doing just before the rise of Islam. And it is interesting: in an area (talking square mileage) a little over a third the size of Dallas, this particular district in Egypt held twenty-nine churches, twenty-five monasteries, seven charitable organizations run by laypeople, and seven hospitals, that’s one hospital for every 5,700 residents—a ratio “lower than anywhere else at any given time before the Industrial Revolution.”[1]

A remarkable detail, which I’ve never forgot ever since first reading it, because it complicates our simplistic notions of progress, the idea that ours is a civilization—of course—more compassionate and more humane, that—of course—we are more morally evolved than our ancestors. Also, because it causes me to wonder about the spirit that gave birth to the moral, philanthropic traditions of the West, and about what will happen to those traditions once that spirit is finally gone—transformed, not for the better, by econometrics, bureaucracy and technology, and a changing view of the human person.

Now the spirit I’m talking about is, of course, Jewish and Christian, born of the book of Deuteronomy, chapter 15, wherein God, having given his people the Promised Land, told them to care for one another, to be a people of equity and compassion, caring for orphan and widow and stranger alike. “[T]here should be no one of you in need,” it says; it’s what Acts of the Apostles quotes directly when describing the Christian community, when Luke writes, “There was no one needy person among them.”[2]

The idea, very simply, is that the people of God, the body of Christ—the elect people rescued by God and brought into the Promised Land, into the Church: these are a people bound together in love backed up by action, love that isn’t just spoken but also made real in solidarity and ethics and even economics. It’s an economics of communion, so to speak, that we find in the Bible, different from the economics of patronage and imperial taxation of ancient Rome.[3] It’s not communism as people sometimes mistakenly say. Rather, the idea is simple: if we are brothers and sisters in Christ, then we ought to act like it, caring for one another because of it, because Christ loves us all and is in us all, holding us together. That’s why we care for one another, because we belong to one another, belonging to God together.

It’s what Paul was trying to explain to the Corinthians. The Christian community in Jerusalem, you see, was impoverished, suffering; these Christians whom the Corinthians had never met, but whom, nonetheless, belonged to them because they all belonged to Christ. And so Paul’s appeal was simple: if the Corinthians believed in Christ and believed themselves to belong to the body of Christ, then, of course, they would want to take up a collection and help out their fellow Christians who were suffering in Jerusalem—“as you excel in every respect, in faith,” Paul said, “may you excel in this gracious act also.”[4] He was asking Christians in Corinth to put their money where their mouths were. Again, the idea is simple: it’s that we should mean it when we say we love somebody, that we should back up what we say by what we do, that action should follow faith. That is, if we really mean it, if we’re not lying.

But why does any of this matter? What does it mean for us? Well, it matters, whether we’re people of faith or not, because it’s the origin of our one of our better cultural instincts, compassion for the weak and vulnerable, which is not something written into our natures as much as inscribed upon us culturally; and which could very well disappear as the cultures of faith which sustained these instincts disappear (the atheists and the bureaucrats are wrong here both historically and anthropologically). This is why, I would humbly suggest, the presence of the Church and the synagogue still matters in society.

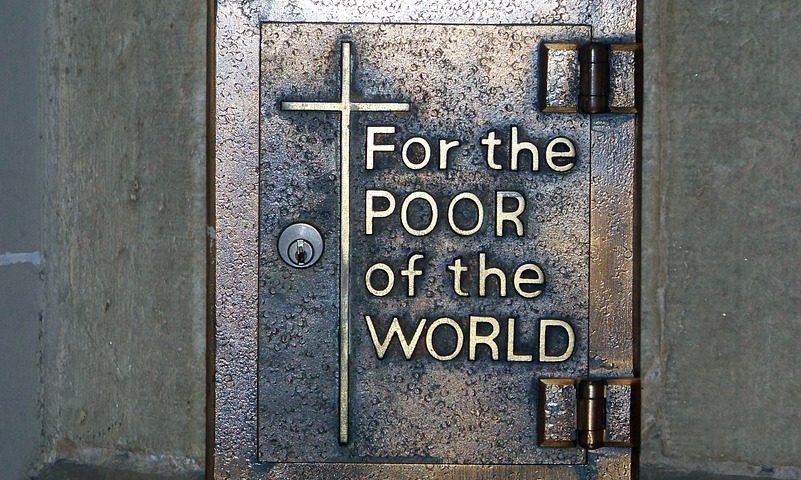

But it also matters for us locally, more immediately, for us as a parish. And that’s because this biblical economics of communion is the reason we ask you to give anything to anything—your parish offering, donations to Vincent de Paul, Catholic Charities, Peter’s Pence. When we talk about money we’re actually talking about people, and about what God wants to do with people, and that’s bring them together to care for them through our care for each other.

There is—you may not want to hear this—a profound relationship between the money you share and the way you care or don’t care for people. There are some, for instance, who object, hem and haw, every time we ask for money—“There they go: they’re asking for money again!” they say—exasperated, offended; some even walk out. But, of course, those folk most of the time don’t give very much anyway; and more importantly and more tragically, they often don’t care as much. They’re the ones, in my experience, most likely to treat the parish like it’s Wal-Mart, in and out as quickly as you can with the sacraments you’ve bought on the cheap. Again, in my experience in pastoral ministry—it’s almost inexorable like some natural law—in things like weddings and funerals: the less invested a person is in the community, personally and financially, the more pushy they are, the more like pure consumers they—the ones who “go to St. Rita,” but heaven help us if anyone knows them, if they’ve given anything since 1982 or paid a visit yet this century.

Now my point isn’t to get on to anyone or complain; nor is my point to ask you for money. In fact, in this area of Christian life, St. Rita fills me with joy more than anything else; so many of you understand this great tradition and are carrying it forward beautifully. My point is that we must always remember that it’s about people: about how God loves people and calls them together to love one another and care for one another, how God calls us together to care for each other. We need always to remember that we must give our hearts to one another, to see and believe in the good of each other, all before we talk about treasure.[5] Otherwise we’re just talking about taxes. Loving God and neighbor with more than our words: that’s what we must be about as a community, trying to become more and more a genuine community. And it’s what you and I must be about as individuals, trying to love the people God’s given us to love more deeply each day.

Because this, my friends, is real Christianity. It’s a loving, giving way of life. And I want us to be real Christians, whom Jesus would recognize as his own. Because that’s good; because it’s the kingdom of heaven. Amen.

[1] Cited in Adam Serfass, “Wine for Widows: Papryological Evidence for Christian Charity in Ancient Egypt,” Wealth and Poverty in Early Church and Society, 101

[2] Deuteronomy 15:4; Acts 4:34

[3] Steven J. Friesen, “Injustice of God’s Will: Early Christian Explanations of Poverty,” Wealth and Poverty in Early Church and Society, 28

[4] 2 Corinthians 8:7

[5] Matthew 6:21

© 2021 Rev. Joshua J. Whitfield