“Before he begins to preach,” St. Augustine taught the would-be preacher, “he should raise his thirsty soul to God in order that he may give forth what he shall drink, or pour out what shall fill him.”[1]

St. Benedict said something similar: “Do not aspire to be called holy before you really are,” he wrote, “but first be holy that you may more truly be called so.”[2] Pretend holiness and self-made piety will not do for the Christian soul. Casual friends and acquaintances may be fooled by it, but in the long run the endurance true sanctification requires will reveal the fraudulent, those wolves and the wicked laid bare for the judgment of God in due time. About the ministers of Christ it is even more dangerous, for pastor and flock alike. Fake sanctity in a pastor is deadly. “[W]hen those who go before lose the light of knowledge,” St. Gregory the Great said, “those who follow are bowed down in carrying the burden of their sins.”[3] Pretend holiness will not do. Rather, genuine holiness and true piety are the goals and gifts of committed Christians: humble, ordinary holiness empty of conceit and ambition. Holiness received not holiness made; holiness that comes as a gift of God: this is the holiness of Christian saints. The holiness Christ offers us.

In this morning’s gospel, the disciples have rejoined the Lord, having been sent out for the first time to anoint, heal, and proclaim repentance.[4] Jesus himself had recently begun his Galilean ministry, inspiring some and provoking others; and now after sending the disciples out to do as he did, he summoned the Twelve back to him and invited them out to a “deserted place” for some rest.[5] Perhaps, like a good teacher, Jesus wanted his disciples to start small. Maybe this was practice evangelism, like a seminarian’s internship, not wanting his disciples to take on too much too soon. Or maybe Jesus was more aware than they of the encircling gloom, that hidden among the fascinated throng were dangerous enemies; perhaps Jesus was calling his little ones back like the Good Shepherd he was.

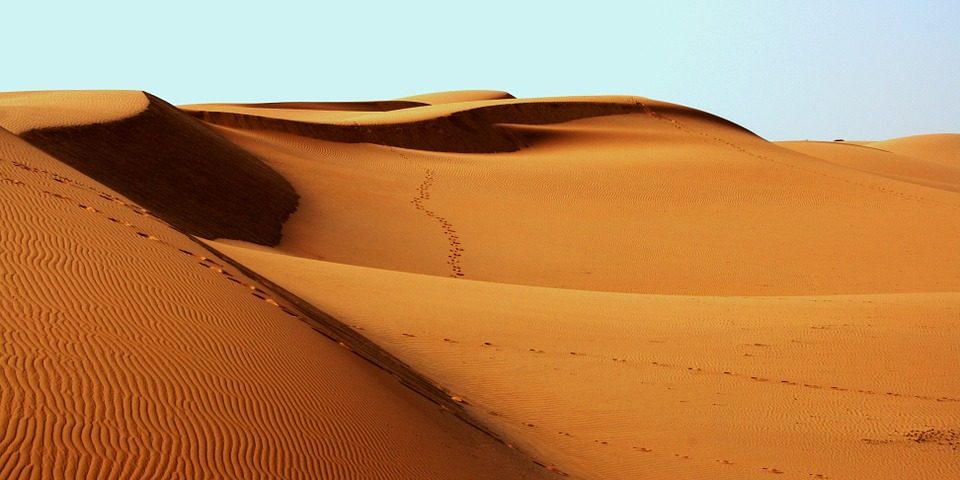

Whatever his reasons, his choice of a “deserted place” is interesting. Mark here evokes the desert, the wilderness, a literal but also a spiritual and conceptual space inscribed by eras of meaning. The desert in Hebrew imagination was at once a dangerous and holy place, a place of both rebellion and redemption. In the desert the Hebrews of Exodus murmured against Moses and Aaron, accusing God in essence of genocide asking, “Why does the Lord bring us into this land, to die by the sword?”[6] Yet, in the prophets, and especially in Hosea, the desert became the imagined place of redemption, the place of God’s renewed seduction of Israel, speaking tenderly to her so that Israel might answer God again “as in the days of her youth.”[7] The desert was a holy place, yet terrifying. In ancient pagan and even Christian imagination the desert was the abode of demons. Ancient Egyptians believed the desert was the dwelling place of Set, the demonic enemy of gods and men.[8] Even after the advent of Christianity in Egypt, it came as no surprise to ancient Christians that Antony went out to the desert to fight demons. Even first century Jews likely imagined beyond the desert horizons demonic forces at work, spiritual enemies and tricksters. It was in the desert that Christ was tempted by Satan because that was Satan’s abode.

So it is not without significance that Jesus brought his disciples out into the desert. He drew the disciples out into the desert to rest, yes; but in drawing them out he also carried them into a place of refinement, a place of spiritual molding and perfection, temptation and challenge. Just as he himself was driven out into the desert to be tempted forty days, refining his mission against satanic attack, so too, perhaps, were the disciples called into the desert to perfect their ministry.[9] But of course the disciples are not met by Satan, but by the crowds. So jostled were Jesus and the disciples, the gospel says, they didn’t even have a chance to eat. So immense were the crowds, Jesus and the Twelve escape by boat in search of their sought-for deserted place. It seems a very human, very convoluted, very messy sort of pilgrimage into the desert. Symbolic, possibly, of the very human, convoluted, and messy pilgrimage that is the Church of Jesus Christ. St. Augustine often found allegories in stories like this. Of the disciples’ haul of fish recorded at both the beginning and end of Jesus’ earthly ministry in Luke and John’s gospels, Augustine discovered the “mystery of the Church” in symbol.[10] And perhaps here too, we might be permitted a little allegory because in the crowded, exhausted, half-apostolic, half-faithful multitudes it is possible to discern our pilgrim Church on earth, that mixed body, Augustine so nakedly described. The apostles, few in number, seeking their protective retreat for the sake of their own ministry, following Christ into the desert; and the crowds, faithful and faithless alike, the deeply devoted and half-interested: this, our Church on earth, drawn out into the desert by Christ. This Church, this pilgrim Catholic Church, our mother, the woman who escaped into the desert.[11]

And for what? Why this pilgrimage? The gospel at this point is clear. Seeing the multitudes, Mark writes, Jesus’ “heart was moved with pity for them, for they were like sheep without a shepherd; and he began to teach them many things.”[12] In the desert, a place at once dangerous and holy, the Logos of God teaches his people; the Holy One of Israel is again with his people, alluring them afresh as Hosea prophesied. In the desert the followers of Jesus once more strike out in exodus, a more perfect exodus, soon to receive a more perfect gift of bread, no mere manna, but word and sacrament bestowed by the Holy One of Israel, Jesus of Nazareth. With Christ, the desert is exorcised, the demonic is vanquished and the rebellious is redeemed. In this gospel image of the Church we can discern the deeper meaning of our Catholic altars: We, the people of God, the Church on earth, follow Christ into the desert, and we are taught by him, and we receive his bread, his flesh, our Holy Communion in this dangerous and holy place. “You spread the table before me in the sight of my foes; you anoint my head with oil; my cup overflows.”[13] In this dangerous place we have our Lord. You hear him. You consume him. “Blessed are those called to the supper of the Lamb.”

The desert has often been a necessary place in the history of the Church: in Egypt, Palestine, Asia, Europe, and America. And just at Antony was bidden to go out and seek the “inner mountain,” so too may the Church be called out into the desert today.[14] You, the Christian soul, may be called out into the desert of your own redemption. The time of spiritual perfection is always at hand. Whatever the case may be for the Church or for you individually, my brothers and sisters, know that Christ is in the desert with you. He has brought you here. Listen to what he teaches you, and eat the bread he offers, because it is here in the desert with him that your holiness will be made genuine, receiving it like a gift. Here with him you will be made his witnesses: apostles, evangelists, teachers, martyrs. Here with him in the desert, you will commune with him and finally know the love of God.

[1] On Christian Doctrine 4.15.32

[2] The Rule 4

[3] Pastoral Care 1.1

[4] Mark 6:12-13

[5] Mark 6:31

[6] Numbers 14:3

[7] Hosea 2:14-15

[8] A-Z of Patristic Theology, 99

[9] Cf. Luke 4:1-11

[10] Tractates on John’s Gospel 122.1

[11] Revelation 12:6

[12] Mark 6:34

[13] Psalm 23:5

[14] The Life of Antony 49

© 2021 Rev. Joshua J. Whitfield