Making readers like me of George Orwell or Yevgeny Zamyatin highly uncomfortable, a San Diego company has developed a technology to monitor social distance. Already in use in some places, it’s called Active Distance Alert and Monitoring, or ADAM, eerily, for short. The technology maps signals emitted by phones, so that crowded areas like grocery stores or parks, gatherings can be safely and softly proctored. All, ostensibly, because of COVID-19. For the sake of public health.

Now Orwellian fright aside (which we all ought to have had for years), there is another fear, one unnervingly allusive in the technology called ADAM coming soon to a store near you. And that’s about what’s happening to us as humans, about the next stage of our re-creation in the image of our screens, because of technologies exactly like this.

Because that’s what happening. We’re being remade. It’s a rebirth achieved not by being more thoroughly monitored (we lost that fight long ago), but by what these latest allegedly necessary, technologically enforced measures further erase from our experience, one already endangered, barely noticed but nonetheless fundamental to being human. And that’s the experience of touch: of touching others and being touched.

What if because of this pandemic we lose touch? Literally, sensually. I don’t mean the touch of family and lovers, which at present is safe, but rather the casual touch of strangers and friends. It’s a strangely plausible question in these days of distancing and masks, when Dr. Anthony Fauci says we should “just forget about shaking hands.” Silly some may think, indulgent and not worth worrying about next to the virus itself, next to lives lost and the economy, which may be true. Yet it’s not a meaningless question, wondering how, underneath the changes of our customs, we, as humans, might also be changed.

And thinking about the loss of touch is precisely where first to worry that it might signal some loss of humanity. And that’s because of what touch means for being human. In his book The First Sense, the philosopher Matthew Fulkerson calls touch just that, our “first sense.” The first to develop in utero, he says touch is unique, less separable from the basic human experience of consciousness. That is, through touch, even more than through vision and the other senses, we experience self.

This is but the insight of phenomenologists and existentialists, a few poets, too. “I am my body,” Maurice Merleau-Ponty wrote, quoting his favorite Christian, Gabriel Marcel; his point was that it is always by means of our perceiving bodies, our touch and other senses, that we in fact discover ourselves as persons, as subjects related to the rest of the world. Martin Buber said much the same, calling touch a child’s first instinct. Tiny fingers reaching for her mother is how a child discovers the relations necessary to human development.

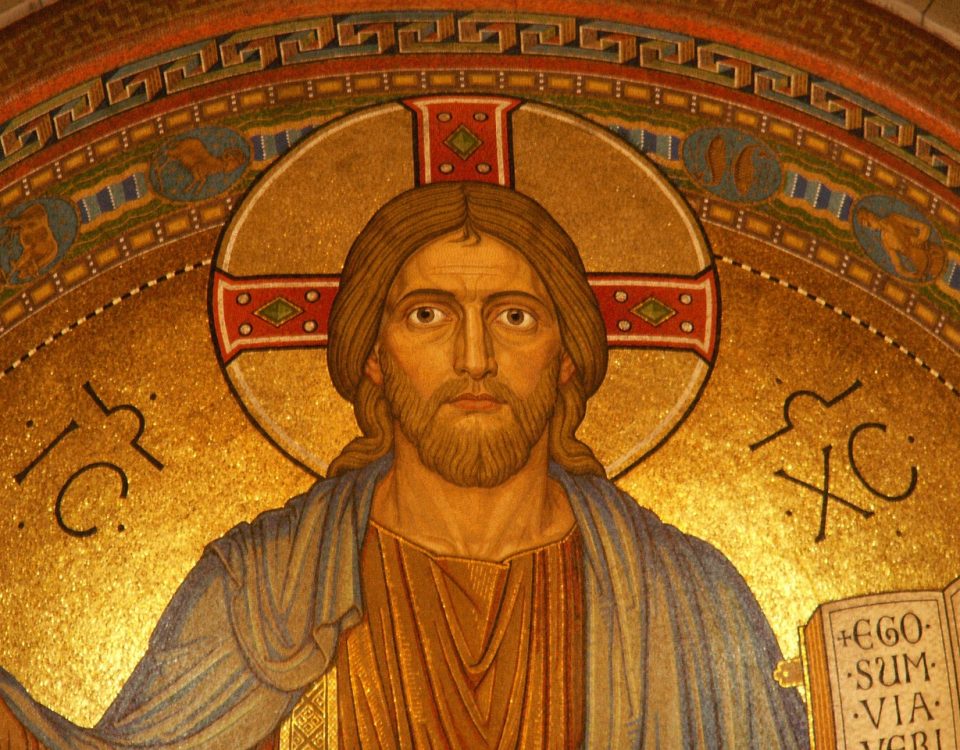

It’s a view essential to Christian thought. Despite surface ambivalence and heretical extremes, at the center of Christianity, of course, is incarnation, a permanent miracle uniting human flesh in a communion of divine nature, rendering all flesh venerable and all touch potentially worship. Think of Michelangelo’s depiction of creation begun by God’s touch. Even for our sexless ascetics, the sensual is not denied but instead transferred to the divine. The same for our metaphysical poets: their denigration of the carnal is always a conceit, for even the likes of John Donne couldn’t deny that love must “take a body, too.” For believers, touch is a sacramental act, necessary not just for life, but eternal life too.

These are beliefs belonging, at least until recently, to our cultural assumptions, that the experience of touch is necessary to being human, that it can even be a path to God. Not merely a religious or philosophical fetish, the value of human touch is precisely what we must keep and not permanently fear. Because it belongs to being human. This, many of our scientists and our cultural gnostics may have difficulty understanding. Which is why we need more than clean science to guide us.

Thus, as we listen to our scientists, we must also listen to our poets. In these pandemic days, for instance, I recommend Walt Whitman. Better than anyone, he represents the humanism me mustn’t lose. “I make holy whatever I touch or am touch’d from,” he wrote. A sensual poetry so at odds with our current situation, he shows how less human we’ve become and what we risk losing further, sealed off behind our screens, locked in our homes. Which is precisely why we should read him, because he can show us the way back to ourselves, his lines a fearless medicine as necessary as any vaccine.

And so, read Whitman: “Touch me, touch the palm of your hand to my body as I pass,/ Be not afraid of my body.” It’s haunting poetry and presently dangerous. Yet the more our pandemic fear is technologically armed and commodified, the more we’ll need words like this to stay human. So that we don’t forget that simple, semidivine experience, which can be lost at a mere six feet and which no image can replace, life-giving human touch. What this virus shouldn’t destroy.

This column originally appeared in the Dallas Morning News.