There’s a story I’ve always liked of an old Egyptian monk, from about 1,400 years ago, living in what today is called Wadi al Natrun, southwest of the city of Alexandria. He stepped out of his cell one night and saw the devil himself handing out gardening implements to all the other monks—shovels, spades, a scythe or two, and so on. It was a curious sight to be sure.

So the monk went up to the devil to inquire the obvious: “What are these?” he asked. The devil, I imagine, must’ve given the curious monk a funny look. “I am presenting the brothers with a distraction,” the devil answered, “to make them less assiduous in glorifying God.”[1] The devil it seems was trying to entice the monks away from the liturgy and their prayers by tempting them with a little gardening. I don’t know if the temptation worked; the story ends right there. But I’ve always liked this brief tale of temptation—it’s different, silly, but also profound if you think about it a little.

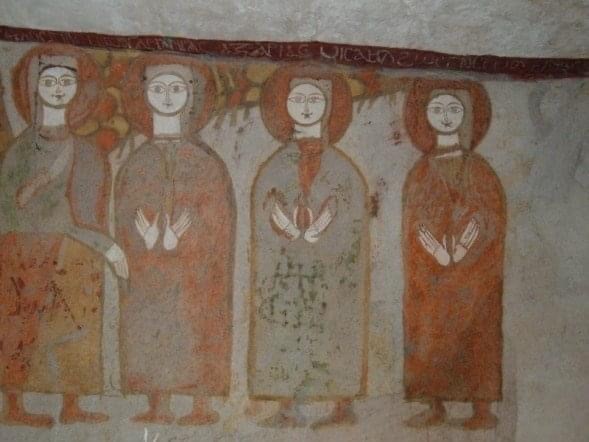

Histories of the desert fathers, those monks of Egypt and Palestine from over a thousand years ago, are full of tales of temptation, tales curious, creative, and even comical. They were tempted by the flesh of course, by demons disguised as “Ethiopian maidens,” for example.[2] But more than that, they were tempted by food; in the desert you could imagine food being more an object of material desire than anything else.[3] It wasn’t flesh but food which the devil used mostly as the means of temptation back then.

And of course the purpose of each temptation was to disrupt the prayer of the monk, the life he’d consecrated to God in his little cave of solitude and silence. One story, for example, about a monk named Nathanael tells of the devil disguised as a little boy, injured and in need of help just outside his cell. Nathanael had sworn to God he would never leave his cell, ever for the rest of his life; but there the child lay hurt begging for help, a dilemma indeed. But Nathanael didn’t give in, he resisted, and so the mirage of the boy, that demon disguised, “dissolved into a dust-storm,” the story goes, and blew away.[4] All the devil wanted to do it seems was to pull that monk out of his cave and away from his prayers.

Distraction is the devil’s game, at least for most of us. Most of us, I doubt, are holy enough or focused enough upon the Lord to merit actual temptation. All that is needed for us is a little advertising, a little suggestion, a little Facebook or Twitter. Which, of course, is nothing new. Spiritual literature both ancient and modern deal with distractions and the random aberrant thoughts which wreck the spiritual life. C. S. Lewis, for example, portrays this brilliantly in The Screwtape Letters when he has Screwtape, the more experienced demon, say to Wormwood his protégé, “A few weeks ago you had to tempt him…but now you find him opening his arms to you and almost begging you to distract his purpose and benumb his heart.” The devil, being utterly powerless, must seduce us away from the Lord somehow. But it doesn’t take much it seems, not actual dramatic temptation really, just a little distraction, subtle and barely noticed. Indeed, it’s the better way to hell according to Screwtape; “the safest road…is the gradual one,” he said, “the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts.”[5] That is the way of damnation—silent, small, slow, inch-by-inch; like texting and driving, you don’t notice it, it’s a smooth ride until it’s too late. Distraction is the devil’s game, and the game is on.

Now I bring this up one, because it’s good for those of us who are sophisticated and comfortable to be reminded from time to time of the devil, of his presence and work; but also because of the gospel we’ve just heard, this passage from Luke.

Jesus is on his way to Jerusalem. Just a little while earlier, he had been transfigured, “dazzling white,” as he spoke with Moses and Elijah about his “exodus,” that is, about what Jesus was to accomplish in Jerusalem.[6] And here in this passage we see Jesus making his way, “resolutely determined,” Luke says; making his way to the temple, to Caiaphas, to Pilate, to Calvary.[7]

And along the way he runs into bigotry, the religious and heretical bigotry of the Samaritans. Jesus was on his way to Jerusalem you see, so they would have nothing to do with him, hating Jews as Samaritans did. The disciples, Jews themselves and likely not very tolerant of Samaritans in return, wanted to call down fire upon them, but Jesus didn’t have time to waste; it was on to the next village, on to the cross and to his death, which in time would heal both petty hatreds.[8]

One would-be disciple speaks up, saying he’ll follow Jesus wherever he goes. But Jesus tells him in substance that following him will bring no worldly rewards, that he’s homeless and that any followers of his should expect the same. Then he runs into another man who wants to bury his father and another who wants to say goodbye to his family. And to these apparently reasonable requests, Jesus gives a rather harsh answer. He says they’re not “fit for the kingdom of God,” that they’re not as determined and dedicated as they should be, and so they shouldn’t even bother.[9] Their hearts aren’t right, not fit for following Jesus.

Even though their concerns at one level are reasonable and respectable—concerns for housing and family and so on—Jesus is saying that in light of the mission, in light of the kingdom, they are no longer as reasonable and respectable as they once were. Jesus here is trying to convert our values and our priorities. He’s trying to bend our hearts and minds toward God and the kingdom, away from the flesh and the world, even from those benign and beautiful parts of the world, even our families and even our homes. Even these must be appreciated now in light of the kingdom, no longer idolized as ends in themselves.

What we see here is the fundamental choice which rests underneath all Christian life, indeed all life. At baptism the Christian turns away from the world, the flesh, and the devil toward Christ and his kingdom. In ancient baptismal liturgies, catechumens literally turned from west to east, symbolizing their renunciation of the devil. It was understood to be a conversion from ugliness to the “truly beautiful.”[10] It was understood to be a conversion from cupiditas to caritas, as Augustine said, from worldly fleshly desire to charity for God and neighbor, learning how to love our neighbor with God and actually in God.[11] It was a conversion of love and therefore a conversion of loves, a reordering of the way we value everything, a reordering of priorities. It was about seeing God as the most important thing there is, not only saying it but meaning it too—letting it change your life.

Now practically what does this mean? It means this: as my dad used to tell me growing up, “If it’s important to you, you’ll be there.” Simple as that. “If it’s important to you, you’ll be there.” He was, of course, teaching me about commitment. If you said you’d do something, do it. Excuses are worthless. In church, in school, in sports, in hobbies—if you say you’ll be there, be there. That is, if it’s important to you. This is the human analogue to what Jesus is telling us about what it means to be a Christian. “If it’s important to you, you’ll be there.” God, prayer, the Church, the sacraments, will take priority in your life. That is, if they’re important to you. Be as sentimental as you want about how much you love Jesus, if that love doesn’t change you, if it doesn’t literally shape your day, then it’s not really love, its flattery. And that’s cheap, worthless even.

This is why that story about the devil passing out gardening tools is so brilliant. Gardening is a good thing to do, it’s fun, useful. But here’s the devil handing out shovels, gift cards to Lowes. The devil’s game is distraction. And we get distracted a lot. Some people don’t make it to Mass on Sunday. They’ve got things to do, good things too. But honestly, after today’s gospel, what do you think Jesus would say about your reasons for not going to Mass? “No sweat, you’ve got a tournament, I understand.” “Yeah, the Mass is too long. 55 minutes is a real beating, a real drain on your time.” You think he’d say that? Really? Have you read the New Testament?

“If it’s important to you, you’ll be there.” That’s just true. It’s not rocket science. That’s true for Mass, for prayer, for your family if you work too much, for your church family, for all those true, good, and godly things. “If it’s important to you, you’ll be there.” If you love Jesus, then you’ll change your life. If you don’t, you won’t. Again, it’s not rocket science. It may be a little blunt, a little hard, but what sort of Jesus do you want? The real one or a soft imitation? I have to report to the real one, though, not to the idol of your sentimentality. And so I speak like the Jesus of the gospels, and that’s sometimes hard. My apologies, but I have no other choice.

Words are important. It’s important what’s in your heart. I’m glad you love Jesus. I’m glad you’re here. But words aren’t all that matter, and the heart is only as good as the sacrifices it makes. I’m glad you love Jesus. I’m glad you’re here. But what do you think Jesus would say to you about your priorities and commitments, about the things you say matter most? Honestly, what would he say? They certainly would be words of love and mercy, but at times they’d probably be hard words too. That’s just the truth—for all of us. And maybe we need a little more of that truth these days—to follow him better, to follow him at all. Amen.

[1] John Moschos, The Spiritual Meadow 55

[2] Palladius, Lausiac History 23

[3] Peter Brown, The Body and Society, 220

[4] Lausiac History 16

[5] C. S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters, Letter XII

[6] Luke 9:29-31

[7] Luke 9:51

[8] Luke 9:52-56

[9] Luke 9:57-62

[10] Pseudo-Dionysius, The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy 393D-396B

[11] Cf. Augustine, City of God 14.7

© 2022 Rev. Joshua J. Whitfield