I always like to sing the Gospel of John on Good Friday, even though it’s long. In exchange I try to preach briefly; at least I try my best.

You see I Like to sing the gospel on Good Friday for good reason, for deeper reasons, I think. Because the gospel needs to be sung, at least now, at least today—again, I think.

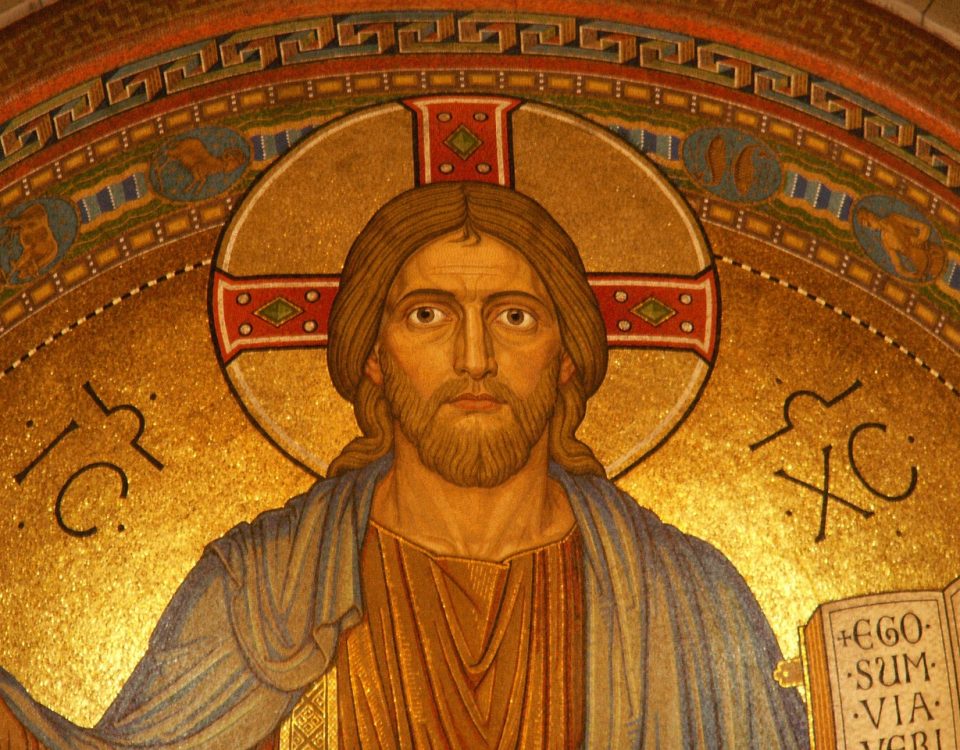

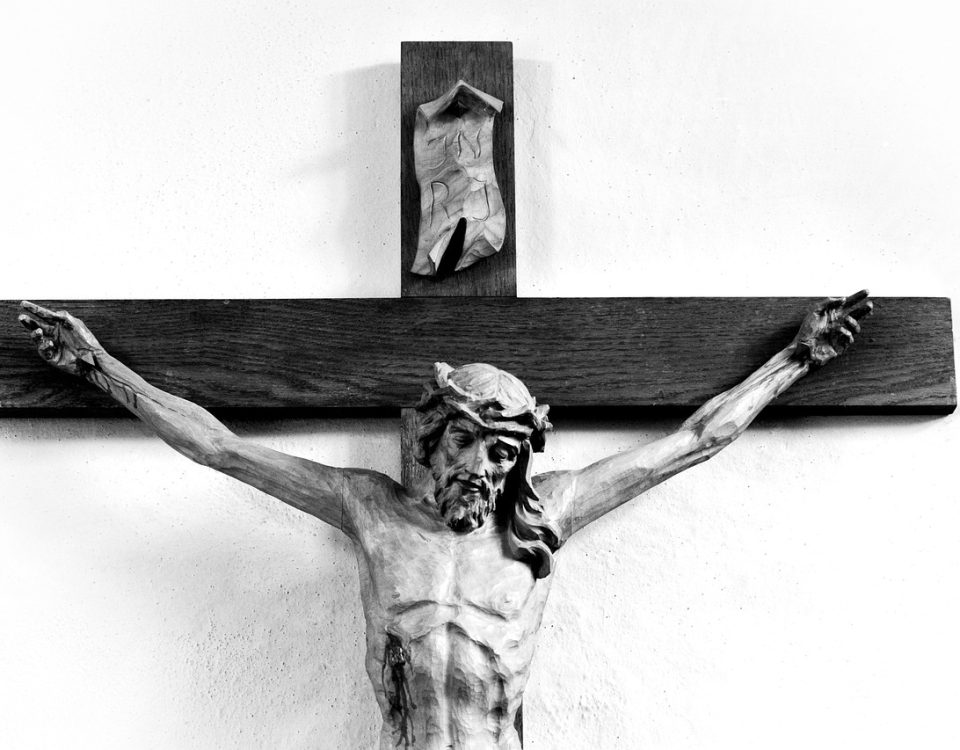

The passion of Christ, as told by John, is a dark story, a story of betrayal and violence, torture and mockery, blasphemy and blindness, the façade of justice and power and the perversion of religion. That is, it’s a human story, as grotesque as anything, an enduring testimony to the pathetic and seemingly eternal recurrence of wickedness and suffering and failure. It’s our story, a parable of the dark truth of us and our world, dark and damnable.

But it’s a story we sing, which we’ve put to music; beautiful music, beautiful voices singing the betrayal, arrest, and death of Jesus. It’s odd to do so, to say the least. Singing about we’ve done to God, our mockery and murder of him.

But here’s the thing, here’s why we sing: because to sing is to hope. We know this is true because we’re human; it belongs to the rhythms and mathematics of our bodies. To sing is to hope. This is almost universally true. Each of us takes comfort in music in some way or the other: the catharsis of a sad song to assuage teenage heartbreak; taps over the grave of the valiant dead; Barber’s Adagio played at the funeral of President Kennedy. Music speaks and heals; there’s something visceral and primeval about it. The ancients thought music was written into the cosmos as well as in us. Music belongs to the elements of existence and history, joy and pain. It has always been so.

The first time we hear of singing in the Bible is on the shores of the Red Sea, the Hebrews, liberated from slavery and the pursuing Egyptians. In the very first moment of their freedom, Moses and the people lifted their voices, “I will sing to the Lord!”[1] It was a song John would hear again in his vision, a song sung by saints in heaven, standing on the shores of a sea of glass mingled with fire, the song of Moses now become the song of the Lamb.[2] A song of liberation and a song of salvation.[3]

It is the most human and at the same time the most divine thing to do: to sing so that we may hope, to sing in this world and to pray. Really, it’s the only thing that makes sense sometimes.

We all see the evil of the world, broken and bloody and cruel. We see the world’s sickness and inhumanity; we witness a global pandemic and global fear, and that too speaks to us, of the coldness and horror and loneliness of existence. And some look at this and in response disbelieve, refusing the immortal longings which belong to them and the God who made them. They practice a sort of academic atheism. They refuse to believe in God in an evil world, for no God would allow this. They don’t sing; they’re silent, saying only that there’s nothing, nothing at all.

But funnily enough that’s not what most sufferers do. Sufferers: they tend to sing. As Pope Benedict XVI said long ago, atheism belongs to the privileged “onlooker.”[4] Those who actually suffer, however, they tend to sing, to pray, to discover God. Even in the senselessness of it, they tend to sing and pray. Gabriel Marcel, that obscure philosopher I like, he said once, “No gesture is more significant than the joined hands of the believer, mutely witnessing that nothing can be done and nothing changed, and that he comes simply to give himself up.”[5]

The lamentations, the cries, the dirges of history, slave songs in the fields, the crimson beauty of our bloody history: these are the songs of believers. Atheists can’t sing the blues. Jesus on the cross: “My God…why have you forsaken me?”[6] These are the songs of suffering, the songs of believers in suffering. It’s singing which began in the mists of time and which continues today.

But, as I said, to sing is to hope. Singing is the beginning of heaven, the beginning of healing and holiness. This is why we sing the gospel today. It’s why we sing anything at all. Because of hope. Singing is how hope becomes more than just an idea. It’s how we come to know hope and to feel it. And it’s why we sing the gospel on Good Friday. Because the world needs hope.

And so, thank you for indulging me, singing the Gospel of John on Good Friday. Long, I know. And I don’t think I preached briefly; I’m sorry about that. But I wanted to sing. I feel we needed to sing. And I hope you want to sing too. Amen.

[1] Exodus 15:1-21

[2] Revelation 15:2-4

[3] Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (Benedict XVI), The Spirit of the Liturgy, 136

[4] Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (Benedict XVI), Dogma and Preaching, 35

[5] Gabriel Marcel, Being and Having, 187

[6] Matthew 27:46

© 2020 Rev. Joshua J. Whitfield