I was in Paris this past week; we visited the Musée d’Orsay. Mostly I wanted to see Van Gogh; some of his paintings are on the top floor of that museum.

Alli and I were in Paris celebrating our 20th anniversary; we just walked around the city all week; our only planned stops, above all, were to visit the Rodin Museum and then to see Van Gogh in the Orsay.

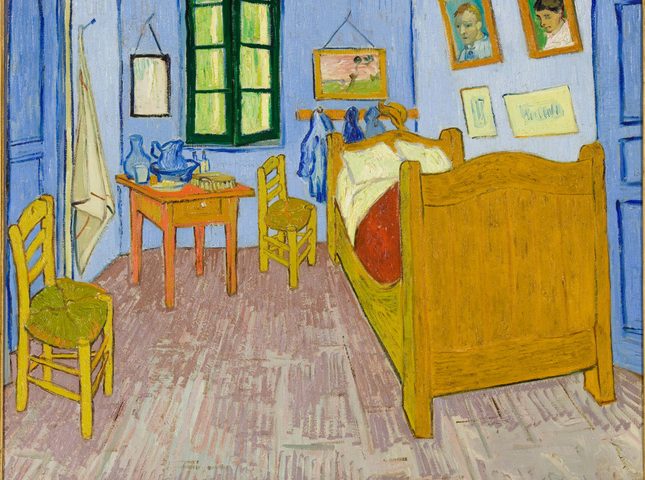

And it was worth it, even amid the crowds of people crowding the most famous works, taking selfies in front of them, stuff like that. It’s good we still swarm about beautiful things even though we don’t quite know how to behave. What I wanted to see in particular was the painting by Van Gogh called The Bedroom, which is a painting of, well, his bedroom. There are a few copies of it, the other, I think, in Chicago. It’s beautiful; you’d recognize it if you saw it: a beautiful blue room with a few pictures on the wall, a chair, a table, a yellow bed. A comfortable little room; it makes you feel comfortable just looking at it. In fact, that’s the effect Van Gogh wanted the painting to give; he wanted whoever looked at it to feel rest. “[T]he picture ought to rest the mind,” he wrote to his brother Theo.[1] And that’s really why I wanted to see it, because the painting does indeed give that—a small bit of rest. It is quite something to experience.

I don’t know, maybe it’s because Van Gogh was so troubled a person, it makes this painting of his bedroom, this painting meant to “rest the mind,” so poignant, almost sad. You see, all his life he struggled to find himself, his purpose. Bright, but not much of a student, he worked unhappily for an art dealer for a time. He thought about being a minister a bit, but he didn’t really care for all the studies that required; he worked for a little while as a missionary among coal miners in Belgium; he even preached a bit. But none of it panned out; he constantly struggled with a sense of failure. Even after his brother encouraged him to pursue his art, he still could never shake his sense of failure. His mental health wasn’t healthy at all; it never got better. The poor man was constantly in search of what he called “simplicity,” constantly in search of rest. But he never found it. At least not in this life; his is a very sad story.

Which is why the painting of his bedroom means so much, a painting meant to “rest the mind.” Because that’s what he was desperately looking for. This was the same time in his life he was looking obsessively to paint stars in the night sky. These now famous paintings about a man’s desperate search for peace now constantly crowded about by selfie-takers: there’s something true and sad about that. I don’t know, it’s just I remain moved by a troubled soul who was simply looking for rest, for peace. That’s how I think Van Gogh is one of us. Because I think that’s true of each of us, even if we can’t describe it or make art out of it: we desire to “rest the mind;” we search for ourselves, our purpose, our peace, and sometimes we can go insane looking for it. Perhaps you know what I’m talking about; perhaps you’re honest enough with yourself, still human enough, to feel what he felt. For we all are looking for that rest; because, of course, we were created for it.

St. Augustine talked about this, didn’t he? Our hearts are restless, he said, until they “rest in thee.”[2] It’s the discomforting feeling each of us has, looking for the Eden we lost. These are our “immortal longings,” Shakespeare called them.[3] Walker Percy simply called it “the Search.”[4] Francis Thompson, another very troubled artist, wrote about the “hound of heaven,” the inescapable search for God; it feels like being hunted sometimes, he said.[5] Again, I’m talking about that deeper feeling, that feeling you get when you’ve turned off the screens, when you’ve stopped performing for the people around you, when you’ve stopped buying things, stopped drinking too much, when you’re quiet and are left to yourself, when you’re at your most silently human. That’s when you feel it, exactly what Van Gogh felt—the desire to “rest the mind.”

Now the reason I bring all this up—and forgive me dwelling on it—is that, well: why have you come to church today? Why go to church at all, ever? Now, there are all sorts of good reasons to go to church, and you should go to church for whatever reason you can think of; even if they’re not all that profound or even good, God will eventually purify those reasons by his very presence. But, for me though, there is something here that touches this deeper desire we all have to “rest the mind.” Paul called it a “peace which passes all understanding.”[6] Jesus called it his yoke and his burden; he called it easy and light. “I will give you rest,” Jesus said.[7] Why have you come to church? Why do I go to church? For me, at least—for this. Because I want that rest; I need this rest; I need Jesus’s rest; I need him. That’s why, out this weary loud world I still go to church, even a broken one. Because I know Jesus, his rest, is here.

But the thing is—and this is the point of today’s gospel—this rest, Jesus’s rest, his kingdom: it’s often hidden.[8] Which means you have to look for it; you have to be the sort of person willing to look for it. Amid all the glamour and noise and gimmicks and cheap answers; amid all the shallow celebrity wit, the politician’s promises; amid all the advertiser’s tricks and strategies of desire; amid all the overdone youth sports tearing families away from the divinely ordained gift of Sunday worship and Sunday rest, that family-destroying, soul-destroying false religion; amid all the things that lure you away from silence and prayer, from the Scripture, from the holy Mass, from the Christ who waits silently for each of us, waiting to be found, our souls will remain restless until we find Christ where he wills to be found. Which is here—in the still holy Catholic Church of God. Which is this Catholic altar from which we are miraculously fed the Word which can still give us peace. Which is why we are here, even if we have yet fully to understand it—this treasure we’ve found to rest the mind. Amen.

[1] Letter 554 [F], The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, 416 (16 October 1888)

[2] Augustine, Confessions 1,1.5

[3] William Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra V.ii

[4] Walker Percy, The Moviegoer, 13

[5] Francis Thompson, “The Hound of Heaven” (1890)

[6] Philippians 4:7

[7] Matthew 11:28-30

[8] Matthew 13:44-46

© 2023 Rev. Joshua J. Whitfield