My wife and I, we have four children, all younger than 7. Ours is not a quiet house.

A house of screaming and a house of endless snot, it’s also a house of love, grown and multiplied every few years. In a house of little sleep, my hobby these days is simply to sit down; fellow parents know what I mean. Just like that loud and beautiful Kelly family gone viral out of South Korea recently, ours is a perfectly normal family, “normal” understood, of course, in relative terms. It’s both exhausting and energizing, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything. It is the form and gift of my life, my family.

But here’s what’s strange about us: I’m a Catholic priest. And that is, as you probably know, mostly a celibate species.

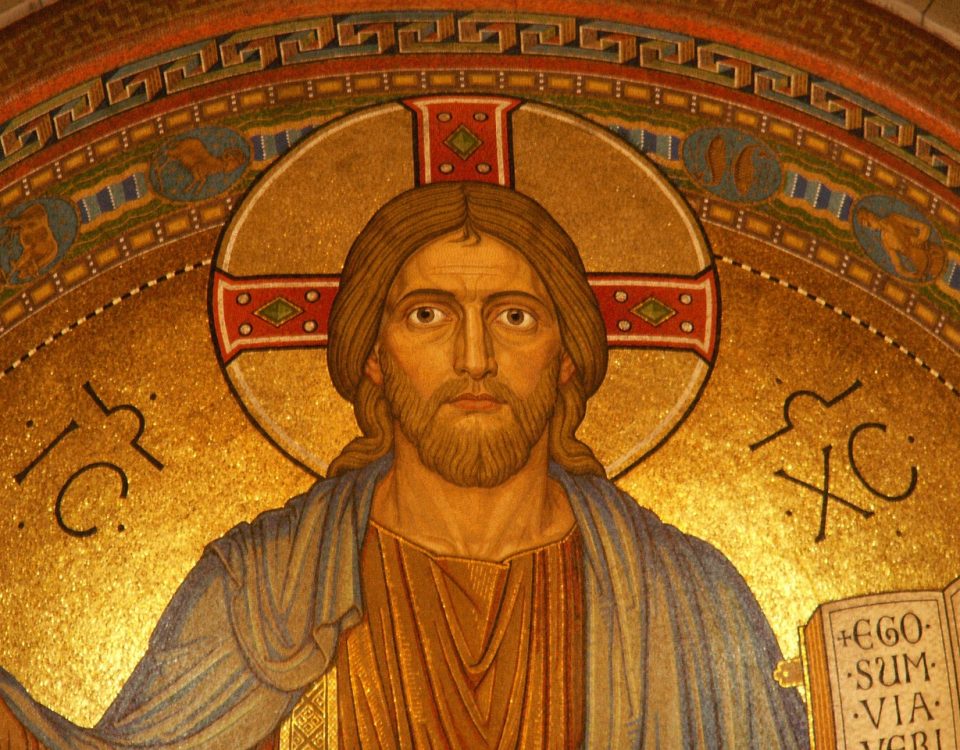

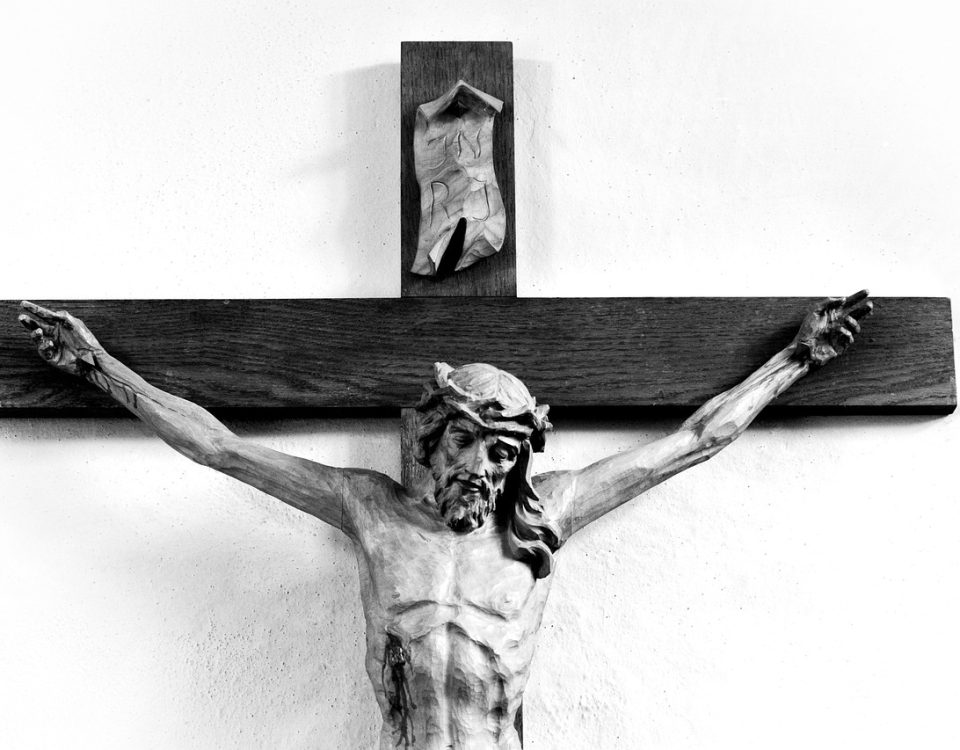

Now the discipline of celibacy, as a Christian practice, is an ancient tradition. Its origins belong to the very mists of early Christianity: to the deserts of Egyptian monasticism, the wilds of ancient Christian Syria and to Luke’s gospel. For priests, celibacy has been the universal legal norm in the Catholic West since the 12th century and the de facto norm long before that. Saint Ambrose in the fourth century, for example, wrote about married priests, saying they were to be found only in “backwoods” churches, certainly not in the churches of Rome or Milan.

Yet there have always been, for good reasons, exceptions made, particularly for the sake of Christian unity. The Eastern Catholic Churches, for example, many with married priests, have since early modernity flourished in the Catholic Church. Likewise for me, a convert from Anglicanism. I’m able to be a Catholic priest because of the Pastoral Provision of Saint John Paul II, which was established in the early 1980s. This provision allows men like me, mostly converts from Anglicanism, to be ordained priests, yet only after receiving a dispensation from celibacy from the pope himself. The Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter in the United States, established by Pope Benedict XVI to provide a path for Anglican communities to become Roman Catholic, is another instance of the Church making an exception, allowing for the same dispensations from celibacy to be granted to priests.

But these are exceptions made, as I said, for the sake of Christian unity, because of Jesus’ final prayer that his disciples be “one.” They do not signal a change in the Catholic Church’s ancient discipline of clerical celibacy.

Now you might be surprised to know most married Catholic priests are staunch advocates of clerical celibacy. I, for one, don’t think the Church should change its discipline here. In fact, I think it would be a very bad idea. Which brings me to my particular bête noire on the subject.

I get that I’m an ecclesiastical zoo exhibit. On my way to celebrate Mass in Saint Peter’s in Rome a few years ago, fully vested in my priestly robes, I had to push my boy in the stroller through that ancient basilica as we made our way to the altar. He had a broken leg, and Alli had the other kids to manage; and so there I was pushing the kid and the purse through Saint Peter’s, wide-eyed tourists’ mouths agape at the sight. It is indeed quite a sight, a life outside the norm.

Even in my own parish, visitors will sometimes sheepishly step forward with curious and concerned questions. “Are those your children?” they’ll ask in whispered tones as if it’s something scandalous, as my kids hide underneath my vestments as if it’s something normal. A zoo exhibit as I said, but I’m happy talking about it, it’s not a problem. It’s just us: Fr. Whitfield, Alli, and all the kids. A perfectly normal, perfectly modern, joyful Catholic family.

But beyond the adorable spectacle, they are the assumptions which follow that frustrate me.

They are very few, of course, who refuse to accept me. Hardened idiosyncratic traditionalists who think they know better than the tradition itself sometimes call it a heresy. This, of course, is nonsense; to which, when such rare criticisms reach me, I always simply invite them to take it up with the pope. He’s the one they should argue with, not me.

Most of the time, however, people see me as some sort of agent of change, the thin end of some wedge, some harbinger of a more enlightened, more modern church. Being a married priest, they assume I’m in favor of opening the priesthood to married men, in favor too perhaps of all sorts of other changes and innovations. This too is an assumption, and not a good one.

Laity who have no real idea of what priesthood entails and even some priests who have no real idea of what married family life entails both assume normalizing married priesthood would bring about a new, better age for the Catholic Church. But it’s an assumption with little supporting evidence. One need only look to the clergy shortage in many Protestant churches to see that opening up clerical ranks doesn’t necessarily bring about spiritual renaissance or growth at all, the opposite being just as likely.

But more importantly, calls to change the discipline of celibacy are usually either ignorant or forgetful of what the church calls the “spiritual fruit” of celibacy, something largely incomprehensible in this libertine age, but which is nonetheless still true and essential to the work of the church. Now being married certainly helps my priesthood, the insights and sympathies gained as both husband and father are sometimes genuine advantages. But that doesn’t call into question the good of clerical celibacy or what my celibate colleagues bring to their ministry. And in any case, it’s holiness that matters most, not marriage or celibacy.

But beyond answering all these scattered arguments, what gets overlooked are the actual reasons people like me become Catholic in first place, as well as the actual reason the Catholic Church sometimes allows married men to be ordained. And that’s Christian unity, to say it yet again.

When you see a married priest, think about the sacrifices he made for what he believes to be the truth. Think about Christian unity, not change. That’s what I wish people would think of when they see me and my family. We became Catholic because my wife and I believe Catholicism is the truth, the fullness of Christianity. And we responded to that truth, which meant (as an Episcopal priest at the time) giving up my livelihood and almost everything I knew. And just as my wife was pregnant with our first child.

Because the Catholic Church believes Christians should be united, it sometimes makes exceptions from its own, even ancient, disciplines and norms, in my case celibacy. My family and I are not test subjects in some sort of trial run put on by the Vatican to see whether married priesthood works. Rather, we’re witnesses to the church’s empathy and desire for unity. That’s what we married priests wish people would see, the Catholicism we fell in love with and made sacrifices for.

And it’s a sacrificial life, one my whole family lives, my wife probably most of all. We’ve never been busier, never more exhausted, but we’ve also never been happier. Even my kids make sacrifices every day for the church. It’s hard sometimes, but we do it, and joyfully; one, because we’ve got a great parish that gets it, and two, because we’re in a church we love and believe in, not a church we want to change.

And that’s the thing: I love the church. We married priests love the church, our families love the church. That’s why we made such sacrifices to become Catholic. And it’s why we love the tradition of clerical celibacy and see no conflict at all with that and our serving as married priests. As Thomas Aquinas said, the church is circumdata varietate, surrounded by variety, a variety bound by charity and truth that only the faithful can see clearly.

Pope Francis’ recent comments in Germany on the prospect of permitting married Catholic men to become priests don’t bother us. Because we understand him and we belong with him in this tradition of charity and truth. This is the necessary mysticism of it, the mysticism without which it cannot be understood, and the mysticism many pundits upon this subject know nothing about.

And it’s also why the church could change its discipline tomorrow, contradicting everything I’ve just written, and it wouldn’t matter. Because again, I love the church, and I appreciate its deeper reasoning. I don’t judge the church by the light of popular opinion or even my own opinions, but rather I judge popular opinion as well as my own by the light of the church’s teaching. That is, I give the church my obedience, that reviled ancient virtue, a virtue difficult to understand these days. Yet it’s the only one whereby to think about things of the church.

So that’s us, the Whitfield family: noisy, beautiful, Catholic and complex. And go ahead and throw newspaper columnist in there too, that’s not normal either. Yet somehow it all works, and we have faith that it’ll somehow keep working. That’s about as much sense as I can put to my life, at least as much as I ever could make of it. But really, it’s up to the church to make sense of it, not me.

My job simply is to be me, a father, a husband, a priest, and faithful as I can be. And in that, I both fail and succeed every day, more times than I can count. Just like you.

This column originally appeared in The Dallas Morning News.