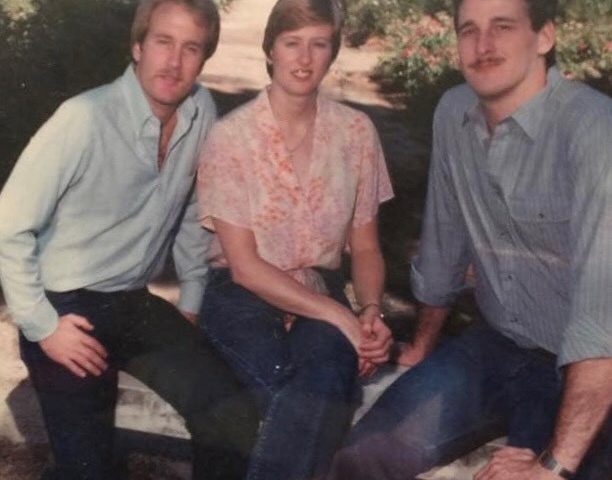

My uncle took my father’s place when my parents divorced.

I was nine when my mom’s younger brother filled the paternal gap. In those poor, stressful, single-parent years, he was our strength. He was a young man, bright and full of life, a gay man and HIV-positive. I loved him deeply because he was there when I needed him. That is, until he died, not yet 30.

His death came at the advent of my adolescence. It was the end of my childish faith. In a few years as a teenager I would renounce Christianity. Living in a small town, I was turned off by what I saw pass for Christianity. It was, I felt, little more than bigotry. Homophobia was only part of it; it belonged to a larger backwardness. If that was Christianity, I thought, I’ll have none of it. To me, it was ugliness, enemy of the love I had known.

In time, I rediscovered my faith. An intellectual journey, theological too, I rejected the phenomena of Christians and instead explored Christianity itself. Instead of listening to Christians, I read the texts: the Bible, early fathers and mothers of Christianity, history, philosophy. That’s what converted me and in the long run made me a Catholic. I found Christianity beautiful once I really saw it.

But my uncle was beautiful too, and a Christian. How to make sense of it, holding together my traditional faith, my orthodoxy and Catholicism, and the experience of my gay uncle’s love? It’s one of the fundamental questions of my life, a tension that remains. For me, for whom only fully theological Christianity inspires anything like faith: How do I keep that faith and remain open to the goodness of people whose lives don’t fit the Catholic moral and theological mold? Can I be a traditional Christian and remain, for instance, in open charity to the experiences of others, especially those in the LGBTQ community? Is such even possible with any sort of integrity?

I think the answer here is that we must accept there are no easy answers, that things don’t fit, that some things in life we may never resolve or understand. I think the answer is that I must learn to live the truth that I don’t know, humbly accepting the possibility I may never know, and that knowing isn’t what matters most.

The martyred monk, Christian de Chergé, is a hero of mine. Fascinated by Islam, he loved the Muslims in Algeria, where he lived. As a Christian, though, he knew he’d never fully understand the role Islam played in the divine plan. “Only death will provide me, I think, the answer I seek,” he said. But the dilemma didn’t turn him into a secular humanist. Rather, he accepted uncertainty while remaining faithful.

“I am convinced,” he said, “that by letting this question haunt me, I am learning to discover the expressions of solidarity.” He called it “existential dialogue.” Instead of trying to figure it all out, he chose to live peaceably and vulnerably, accepting that the best he could do was dream of the time when God would shine his light upon all, “playing with the differences,” Muslims and Christians together.

That’s what authentic Christianity looks like, and it’s how we should exist with our moral disagreements. Not changing the faith, not editing it into something it isn’t, being a Christian means embracing the disjointed tensions of life. It means humbly sitting before the irritating beauty of it all, and waiting for God. It’s why I’m bothered amid our controversies by people of faith and no faith who in their remarkable confidence and certainty seem to have figured it all out, when nobody’s figured it out.

How do I love my gay uncle, for instance, as well as lesbian and transgender people? Do I fundamentally change Christianity? No. Must I therefore damn them to hell? No. What then? The answer is: I don’t know. And I fear those who say they do. And that’s because although messy and aggravating, patience and intellectual humility are better than arrogance. Because it demands we contemplate each other rather than smother differences, that we honor one another by waiting for each other.

But can we as civil society abide this? Rabbi Jonathan Sacks said, “The critical test of any order is: Does it make space for otherness? Does it acknowledge the dignity of difference?” I’m afraid for us the answer is no. We no longer allow things to be disjointed. We no longer abide aporias. We no longer sit with our mysteries.

Which is why we hate more than love, and why violence is what’s become common to us all.

This column originally appeared in The Dallas Morning News.